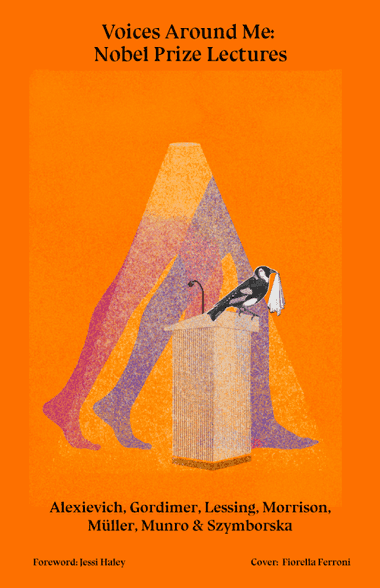

Voices Around Me: Nobel Prize Lectures

Svetlana Alexievich, Nadine Gordimer, Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison, Herta Müller, Alice Munro, Wisława Szymborska

- ISBN: 978-1-961368-11-8

- First published: March 2023

- Publication date: March 2023

Voices Around Me: Nobel Prize Lectures

Svetlana Alexievich, Nadine Gordimer, Doris Lessing, Toni Morrison, Herta Müller, Alice Munro, Wisława Szymborska

Foreword

In 2022, Annie Ernaux became the seventeenth woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. She is also the first French woman, the sixteenth French citizen, the ninety-sixth European, and the 119th person to win. In her acceptance lecture, she outlined how she viewed the context of her win: “I do not regard as an individual victory the Nobel prize that has been awarded me. It is neither from pride nor modesty that I see it, in some sense, as a collective victory.”

Ernaux’s claim of a collective ownership for a highly individualized award echoes ideas shared by many of the women laureates that came before her—as does her emphasis on the tension between the patriarchal system the Nobel stems from (and, to many, still represents) and the structural position of some winners, particularly women. When asked if she anticipated the prize, 2013 laureate Alice Munro replied: “Oh, no, no! I was a woman! . . . I just love the honor, I love it, but I just didn’t think that way.” Learning about her win from a group of reporters as she returned home from a hospital visit, eighty-seven-year-old Doris Lessing was flustered: “They told me a long time ago they didn’t like me and I would never get it. . . . They sent a special official to tell me so.” \[1] Surrounded by snapping cameras, she promised: “I swear I’m going upstairs to find some suitable sentences, which I will be using from now on.”

Beyond a sense of breaking into a boys’ club and the communal weight that comes with this entry, there is little on the surface to connect the Nobel women writers. Writers who win the Nobel Prize must have “in the field of literature, produced the most outstanding work in an idealistic direction.” This is the criteria set in the will of Alfred Nobel, a Swede who perhaps changed the world most by inventing dynamite. Though his own professional domain was destruction, he wanted his namesake prize to recognize people whose work has “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

This edict applies vague gravity and hefty responsibilities to the laureates. Women who have won the literature prize have been assigned roles like “the epicist of female experience” or the “Geiger counter of apartheid.”\[2] They are understood to represent specific nations, ideologies, and generations. At the same time, they must represent all of us (particularly all women); they must, with their words, illuminate the universal via the specific.\[3]

Laureates are chosen by a committee whose membership draws from The Swedish Academy, a group of eighteen literary professionals (De Aderton, “The Eighteen”) with a lifetime tenure.\[4] The academy was installed by King Gustav III in 1786, so it predates the Nobel Foundation by 115 years. The committee selected the first woman Nobel laureate eight years into the existence of the award. This was five years before they ever elected a woman to their ranks (the same woman in both cases: Selma Lagerlöf, who borrowed from realism but returned to the romantic in her folkloric fiction).

Alfred Nobel chose the Swedish Academy as the arbiter of the literature prize, just as he chose groups to select laureates from the other categories (chemistry, peace, medicine, economics). His only instruction for the committees was that, in their deliberations, “no consideration be given to nationality, but that the prize be awarded to the worthiest person, whether or not they are Scandinavian.”

So, with minimal-yet-lofty guidance, a nineteenth-century armaments tycoon bequeathed a prize that still inspires fierce arguments, intense celebration, and online gambling across the globe. Of course, geography and international politics are inextricably linked to all Nobel Prizes, with literature proving no exception. Too European, too white, too male, too contrary to, or too swayed by illusory cultural tides—criticisms of the committee’s choices abound annually. Summaries of who the laureates are and where they come from arguably reach more people than the winners’ written works, making identity and nationality a major part of each award.\[5]

Though Lägerlof won in 1909, nearly half of the total awards to women are concentrated in just the last eighteen years.\[6] Most of the women laureates are from Europe, as are most literature laureates in general. The first Latin American author ever to win was a woman (Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral, awarded 1945), and she remains the only Latin American woman awarded. American novelist Toni Morrison is the only Black woman recognized to date, and the body of winners remains overwhelmingly white. In terms of lived experience, the winners have faced famine, war, displacement, illicit romance, racism, motherhood, prestige, derision, and more.

What does it mean for a woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature—for the life and work of the writer? For some, like Belarusian Svetlana Alexievich (inventor of “the documentary novel”) and Austrian poet and novelist Herta Müller, it means sudden visibility: newspaper coverage, reprints, new translations. For others (Lessing, Morrison and South African novelist Nadine Gordimer), it’s a capstone in a monumental career that people have been predicting for years. For all of them, it means roughly one million dollars in prize money and at least a temporary surge in book sales. And it is perhaps a varied experience for the winner personally. Wisława Szymborska’s friends called her win “the Nobel tragedy” because the intensely private Polish poet was unable to write for years after the onslaught of attention. Meanwhile, Morrison gathered friends to celebrate with her in Stockholm. “I like the Nobel Prize,” she said. “Because they know how to give a party.” \[7] Winning the prize in 2015 did not protect Alexievich from being forced into her second exile in 2020. Facing abduction and arrest, she fled—leaving behind manuscripts, her home, and a part of the world whose story she invented a new genre to tell.\[8]

No matter what the recognition means for these women personally, their names will always be paired with the phrase “Nobel Prize winner” whenever they appear in print. No matter what prospective readers understand about the Nobel Prize’s history, process, and statistics, this moniker will likely suggest to them something important about the writers’ work. And no matter where the writer is from, no matter what or who they write about, in accepting the prize they all accept a huge task: finding the “suitable sentences” to deliver a lecture (or, in Munro’s case, a conversation) that articulates the importance of literature and the meaning of their own life’s work.

Read together, the reflections of the Nobel women reveal a range of ideas about what literature can do and a sense of a practitioner’s responsibility to these ideas. While the lectures vary widely in content—from Lessing’s and Gordimer’s concrete political lessons to Szymborska’s larger abstract musings to fables personal (Müller) and universal (Morrison)—each contains observations that are at once totally complex and recognizably true.

With characteristic directness, “master of the contemporary short story” Munro asserts that she knew she could write about small-town Canadian life because: “I think any life can be interesting, any surroundings can be interesting.”

Morrison, whose novels explore so many facets of Black American life with language that is as precise as it is poetic, argues that “language can never live up to life once and for all. Nor should it...Its force, its felicity is in its reach toward the ineffable.”

Lessing, so often setting a prickly (sometimes cynical) tone in her novels of frustrated politics, colonialism, and imagined futures, is hopeful: “It is our stories that will recreate us, when we are torn, hurt, even destroyed. It is the storyteller, the dream-maker, the myth-maker, that is our phoenix, that represents us at our best, and at our most creative.”

Müller’s work paints visceral, impressionistic scenes of stifled lives under Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship in Romania. No stranger to having words withheld, she explains: “After all, the more words we are allowed to take, the freer we become.”

“In the language of poetry, where every word is weighed, nothing is usual or normal . . . not a single existence, not anyone’s existence in this world.” Only Szymborska, who once wrote “After every war / someone has to tidy up,” can be so gentle and so firm at the same time.

Gordimer, whose novels dissect the human wreckage wrought by institutionalized racism and cycles of violence, confirms that “writing is always and at once an exploration of self and of the world; of individual and collective being.”

Each writer’s Nobel lecture includes something that could be applied across the work of the other women who have won, something that collects the individual work under an umbrella of “benefit to humankind.” Each writer explains, in a way reflective of her style, time, place, and politics, how recognition of her work is part of a long, shared story. But if any of the lectures contains something akin to a slogan, it must be Alexievich’s (fitting for a writer whose work, at its core, is aimed at weaving disparate perspectives into an intricate whole). In accepting the prize, she reminds readers and writers alike: “I do not stand alone at this podium. . . . There are voices around me, hundreds of voices.”

Through our work, Cita Press honors the principles of decentralization, collective knowledge production, and equitable access to knowledge. The pieces brought together here reflect these values in ways that represent each writer’s unique commitments, experiences, and style. Our mission is to make the work of women from the past and present visible, and to illuminate the long and diverse history of feminist thought and art. The Nobel Prize gave a huge platform to the writers collected here, and it feels important to think about how this rarefied group of women frame their own legacies, and how they speak to each other from the same stage across the years. We present this book—free, online first, and with a cover by Fiorella Ferroni—with the open invitation to share in these women’s work and ideas. We hope you return to these pieces, together and apart, often or sometimes, but always with the understanding that there are voices around us, and that language gives us a chance to speak and also to listen.

Jessi Haley is editorial coordinator for Cita Press. Cita thanks the Nobel Foundation for the permission to publish these pieces.

\[1] See the full clip "Doris Lessing on the Nobel Prize" from The New York Times (November 17,2013). Reuters, Copyright The New York Times, 2013.

\[2] From the Nobel Committee, for Doris Lessing and Nadine Gordimer, respectively.

\[3] As the children in Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize lecture demand: “Tell us what it is to be a woman so that we may know what it is to be a man. What moves at the margin. What it is to have no home in this place. To be set adrift from the one you knew. What it is to live at the edge of towns that cannot bear your company.”

\[4] As of 2022, the roster of Swedish Academy members joined the body between 1980 and 2020; the majority of the current Nobel Committee is made up of recently elected members.

\[5] (Except for probably in the case of Bob Dylan!)

\[6] The full list of winners, countries, and years: Selma Lagerlof (1909, Sweden), Grazia Deledda (1926, Italy), Sigrid Undset (1928, Norway), Pearl Buck (1938, US), Gabriela Mistral (1945, Chile), Nelly Sachs (1966, Sweden), Nadine Gordimer (1991, South Africa), Toni Morrison (1993, US), Wisława Szymborska (1996, Poland), Elfriede Jelinek (2004, Austria), Doris Lessing (2007, England), Herta Müller (2009, Germany), Alice Munro (2013, Canada), Svetlana Alexievich (2015, Belarus), Olga Tokarczuk (2018, Poland), Louise Glück (2020, US), and Annie Ernaux (2022, France).

\[7] From “Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am” (dir. Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, 2019). In the same clip, Fran Liebovitz said “I highly recommend you have a friend who wins the Nobel Prize.”

8] José Vergara,“On the Dangers of Greatness: A Conversation with Svetlana Alexievich.” Literary Hub, June 3, 2022.

Voices Around Me: Nobel Lectures

NADINE GORDIMER, 1991

Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1991

WRITING & BEING

In the beginning was the Word.

The Word was with God, signified God’s Word, the word that was Creation. But over the centuries of human culture the word has taken on other meanings, secular as well as religious. To have the word has come to be synonymous with ultimate authority, with prestige, with awesome, sometimes dangerous persuasion, to have Prime Time, a TV talk show, to have the gift of the gab as well as that of speaking in tongues. The word flies through space, it is bounced from satellites, now nearer than it has ever been to the heaven from which it was believed to have come. But its most significant transformation occurred for me and my kind long ago, when it was first scratched on a stone tablet or traced on papyrus, when it materialized from sound to spectacle, from being heard to being read as a series of signs, and then a script; and travelled through time from parchment to Gutenberg. For this is the genesis story of the writer. It is the story that wrote her or him into being.

It was, strangely, a double process, creating at the same time both the writer and the very purpose of the writer as a mutation in the agency of human culture. It was both ontogenesis as the origin and development of an individual being, and the adaptation, in the nature of that individual, specifically to the exploration of ontogenesis, the origin and development of the individual being. For we writers are evolved for that task. Like the prisoners incarcerated with the jaguar in Borges’ story \\\\[1], ‘The God’s Script’, who was trying to read, in a ray of light which fell only once a day, the meaning of being from the marking on the creature’s pelt, we spend our lives attempting to interpret through the word the readings we take in the societies, the world of which we are part. It is in this sense, this inextricable, ineffable participation, that writing is always and at once an exploration of self and of the world; of individual and collective being.

Being here.

Humans, the only self-regarding animals, blessed or cursed with this torturing higher faculty, have always wanted to know why. And this is not just the great ontological question of why we are here at all, for which religions and philosophies have tried to answer conclusively for various peoples at various times, and science tentatively attempts dazzling bits of explanation we are perhaps going to die out in our millennia, like dinosaurs, without having developed the necessary comprehension to understand as a whole. Since humans became self-regarding they have sought, as well, explanations for the common phenomena of procreation, death, the cycle of seasons, the earth, sea, wind and stars, sun and moon, plenty and disaster. With myth, the writer’s ancestors, the oral story-tellers, began to feel out and formulate these mysteries, using the elements of daily life – observable reality – and the faculty of the imagination – the power of projection into the hidden – to make stories.

Roland Barthes \\\\[2] asks, ‘What is characteristic of myth?’ And answers: ‘To transform a meaning into form.’ Myths are stories that mediate in this way between the known and unknown. Claude Levi-Strauss \\\\[3] wittily de-mythologizes myth as a genre between a fairy tale and a detective story. Being here; we don’t know who-dun-it. But something satisfying, if not the answer, can be invented. Myth was the mystery plus the fantasy – gods, anthropomorphized animals and birds, chimera, phantasmagorical creatures – that posits out of the imagination some sort of explanation for the mystery. Humans and their fellow creatures were the materiality of the story, but as Nikos Kazantzakis \\\\[4] once wrote, ‘Art is the representation not of the body but of the forces which created the body.’

There are many proven explanations for natural phenomena now; and there are new questions of being arising out of some of the answers. For this reason, the genre of myth has never been entirely abandoned, although we are inclined to think of it as archaic. If it dwindled to the children’s bedtime tale in some societies, in parts of the world protected by forests or deserts from international megaculture it has continued, alive, to offer art as a system of mediation between the individual and being. And it has made a whirling comeback out of Space, an Icarus in the avatar of Batman and his kind, who never fall into the ocean of failure to deal with the gravity forces of life. These new myths, however, do not seek so much to enlighten and provide some sort of answers as to distract, to provide a fantasy escape route for people who no longer want to face even the hazard of answers to the terrors of their existence. (Perhaps it is the positive knowledge that humans now possess the means to destroy their whole planet, the fear that they have in this way themselves become the gods, dreadfully charged with their own continued existence, that has made comic-book and movie myth escapist.) The forces of being remain. They are what the writer, as distinct from the contemporary popular mythmaker, still engage today, as myth in its ancient form attempted to do.

How writers have approached this engagement and continue to experiment with it has been and is, perhaps more than ever, the study of literary scholars. The writer in relation to the nature of perceivable reality and what is beyond – imperceivable reality – is the basis for all these studies, no matter what resulting concepts are labelled, and no matter in what categorized microfiles writers are stowed away for the annals of literary historiography. Reality is constructed out of many elements and entities, seen and unseen, expressed, and left unexpressed for breathing-space in the mind. Yet from what is regarded as old-hat psychological analysis to modernism and post-modernism, structuralism and poststructuralism, all literary studies are aimed at the same end: to pin down to a consistency (and what is consistency if not the principle hidden within the riddle?); to make definitive through methodology the writer’s grasp at the forces of being. But life is aleatory in itself; being is constantly pulled and shaped this way and that by circumstances and different levels of consciousness. There is no pure state of being, and it follows that there is no pure text, ‘real’ text, totally incorporating the aleatory. It surely cannot be reached by any critical methodology, however interesting the attempt. To deconstruct a text is in a way a contradiction, since to deconstruct it is to make another construction out of the pieces, as Roland Barthes \\\\[5] does so fascinatingly, and admits to, in his linguistic and semantical dissection of Balzac’s story, ‘Sarrasine’. So the literary scholars end up being some kind of storyteller, too.

Perhaps there is no other way of reaching some understanding of being than through art? Writers themselves don’t analyze what they do; to analyze would be to look down while crossing a canyon on a tightrope. To say this is not to mystify the process of writing but to make an image out of the intense inner concentration the writer must have to cross the chasms of the aleatory and make them the word’s own, as an explorer plants a flag. Yeats’ inner ‘lonely impulse of delight’ in the pilot’s solitary flight, and his ‘terrible beauty’ born of mass uprising, both opposed and conjoined; E. M. Forster’s modest ‘only connect’; Joyce’s chosen, wily ‘silence, cunning and exile’; more contemporary, Gabriel García Márquez’s labyrinth in which power over others, in the person of Simon Bolivar, is led to the thrall of the only unassailable power, death – these are some examples of the writer’s endlessly varied ways of approaching the state of being through the word. Any writer of any worth at all hopes to play only a pocket-torch of light – and rarely, through genius, a sudden flambeau – into the bloody yet beautiful labyrinth of human experience, of being.

Anthony Burgess \\\\[6] once gave a summary definition of literature as ‘the aesthetic exploration of the world’. I would say that writing only begins there, for the exploration of much beyond, which nevertheless only aesthetic means can express.

How does the writer become one, having been given the word? I do not know if my own beginnings have any particular interest. No doubt they have much in common with those of others, have been described too often before as a result of this yearly assembly before which a writer stands. For myself, I have said that nothing factual that I write or say will be as truthful as my fiction. The life, the opinions, are not the work, for it is in the tension between standing apart and being involved that the imagination transforms both. Let me give some minimal account of myself. I am what I suppose would be called a natural writer. I did not make any decision to become one. I did not, at the beginning, expect to earn a living by being read. I wrote as a child out of the joy of apprehending life through my senses – the look and scent and feel of things; and soon out of the emotions that puzzled me or raged within me and which took form, found some enlightenment, solace and delight, shaped in the written word. There is a little Kafka \\\\[7] parable that goes like this; ‘I have three dogs: Hold-him, Seize-him, and Nevermore. Hold-him and Seize-him are ordinary little Schipperkes and nobody would notice them if they were alone. But there is Nevermore, too. Nevermore is a mongrel Great Dane and has an appearance that centuries of the most careful breeding could never have produced. Nevermore is a gypsy.’ In the small South African gold-mining town where I was growing up I was Nevermore the mongrel (although I could scarcely have been described as a Great Dane …) in whom the accepted characteristics of the townspeople could not be traced. I was the Gypsy, tinkering with words second-hand, mending my own efforts at writing by learning from what I read. For my school was the local library. Proust, Chekhov and Dostoevsky, to name only a few to whom I owe my existence as a writer, were my professors. In that period of my life, yes, I was evidence of the theory that books are made out of other books . . . But I did not remain so for long, nor do I believe any potential writer could.

With adolescence comes the first reaching out to otherness through the drive of sexuality. For most children, from then on the faculty of the imagination, manifest in play, is lost in the focus on day dreams of desire and love, but for those who are going to be artists of one kind or another the first life-crisis after that of birth does something else in addition: the imagination gains range and extends by the subjective flex of new and turbulent emotions. There are new perceptions. The writer begins to be able to enter into other lives. The process of standing apart and being involved has come.

Unknowingly, I had been addressing myself on the subject of being, whether, as in my first stories, there was a child’s contemplation of death and murder in the necessity to finish off, with a death blow, a dove mauled by a cat, or whether there was wondering dismay and early consciousness of racism that came of my walk to school, when on the way I passed storekeepers, themselves East European immigrants kept lowest in the ranks of the Anglo-Colonial social scale for whites in the mining town, roughly those whom colonial society ranked lowest of all, discounted as less than human – the black miners who were the stores’ customers. Only many years later was I to realize that if I had been a child in that category – black – I might not have become a writer at all, since the library that made this possible for me was not open to any black child. For my formal schooling was sketchy, at best.

To address oneself to others begins a writer’s next stage of development. To publish to anyone who would read what I wrote. That was my natural, innocent assumption of what publication meant, and it has not changed , that is what it means to me today, in spite of my awareness that most people refuse to believe that a writer does not have a particular audience in mind; and my other awareness: of the temptations, conscious and unconscious, which lure the writer into keeping a corner of the eye on who will take offense, who will approve what is on the page – a temptation that, like Eurydice’s straying glance, will lead the writer back into the Shades of a destroyed talent.

The alternative is not the malediction of the ivory tower, another destroyer of creativity. Borges once said he wrote for his friends and to pass the time. I think this was an irritated flippant response to the crass question – often an accusation – ‘For whom do you write?’, just as Sartre’s admonition that there are times when a writer should cease to write, and act upon being only in another way, was given in the frustration of an unresolved conflict between distress at injustice in the world and the knowledge that what he knew how to do best was write. Both Borges and Sartre, from their totally different extremes of denying literature a social purpose, were certainly perfectly aware that it has its implicit and unalterable social role in exploring the state of being, from which all other roles, personal among friends, public at the protest demonstration, derive. Borges was not writing for his friends, for he published and we all have received the bounty of his work. Sartre did not stop writing, although he stood at the barricades in 1968.

The question of for whom do we write nevertheless plagues the writer, a tin can attached to the tail of every work published. Principally it jangles the inference of tendentiousness as praise or denigration. In this context, Camus \\\\[8] dealt with the question best. He said that he liked individuals who take sides more than literatures that do. ‘One either serves the whole of man or does not serve him at all. And if man needs bread and justice, and if what has to be done must be done to serve this need, he also needs pure beauty which is the bread of his heart.’ So Camus called for ‘Courage in and talent in one’s work.’ And Márquez \\\\[9] redefined tender fiction thus: The best way a writer can serve a revolution is to write as well as he can.

I believe that these two statements might be the credo for all of us who write. They do not resolve the conflicts that have come, and will continue to come, to contemporary writers. But they state plainly an honest possibility of doing so, they turn the face of the writer squarely to her and his existence, the reason to be, as a writer, and the reason to be, as a responsible human, acting, like any other, within a social context.

Being here: in a particular time and place. That is the existential position with particular implications for literature. Czeslaw Milosz \\\\[10] once wrote the cry: ‘What is poetry which does not serve nations or people?’ and Brecht \\\\[11] wrote of a time when ‘to speak of trees is almost a crime’. Many of us have had such despairing thoughts while living and writing through such times, in such places, and Sartre’s solution makes no sense in a world where writers were – and still are – censored and forbidden to write, where, far from abandoning the word, lives were and are at risk in smuggling it, on scraps of paper, out of prisons. The state of being whose ontogenesis we explore has overwhelmingly included such experiences. Our approaches, in Nikos Kazantzakis’ \\\\[12] words, have to ‘make the decision which harmonizes with the fearsome rhythm of our time.’

Some of us have seen our books lie for years unread in our own countries, banned, and we have gone on writing. Many writers have been imprisoned. Looking at Africa alone – Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Jack Mapanje, in their countries, and in my own country, South Africa, Jeremy Cronin, Mongane Wally Serote, Breyten Breytenbach, Dennis Brutus, Jaki Seroke: all these went to prison for the courage shown in their lives, and have continued to take the right, as poets, to speak of trees. Many of the greats, from Thomas Mann to Chinua Achebe, cast out by political conflict and oppression in different countries, have endured the trauma of exile, from which some never recover as writers, and some do not survive at all. I think of the South Africans, Can Themba, Alex la Guma, Nat Nakasa, Todd Matshikiza. And some writers, over half a century from Joseph Roth to Milan Kundera, have had to publish new works first in the word that is not their own, a foreign language.

Then in 1988 the fearsome rhythm of our time quickened in an unprecedented frenzy to which the writer was summoned to submit the word. In the broad span of modern times since the Enlightenment writers have suffered opprobrium, bannings and even exile for other than political reasons. Flaubert dragged into court for indecency, over Madame Bovary, Strindberg arraigned for blasphemy, over Marrying, Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover banned – there have been many examples of so-called offense against hypocritical bourgeois mores, just as there have been of treason against political dictatorships. But in a period when it would be unheard of for countries such as France, Sweden and Britain to bring such charges against freedom of expression, there has risen a force that takes its appalling authority from something far more widespread than social mores, and far more powerful than the power of any single political regime. The edict of a world religion has sentenced a writer to death.

For more than three years, now, wherever he is hidden, wherever he might go, Salman Rushdie has existed under the Muslim pronouncement upon him of the fatwa. There is no asylum for him anywhere. Every morning when this writer sits down to write, he does not know if he will live through the day; he does not know whether the page will ever be filled. Salman Rushdie happens to be a brilliant writer, and the novel for which he is being pilloried, The Satanic Verses, is an innovative exploration of one of the most intense experiences of being in our era, the individual personality in transition between two cultures brought together in a post-colonial world. All is re-examined through the refraction of the imagination; the meaning of sexual and filial love, the rituals of social acceptance, the meaning of a formative religious faith for individuals removed from its subjectivity by circumstance opposing different systems of belief, religious and secular, in a different context of living. His novel is a true mythology. But although he has done for the postcolonial consciousness in Europe what Gunter Grass did for the post-Nazi one with The Tin Drum and Dog Years, perhaps even has tried to approach what Beckett did for our existential anguish in Waiting For Godot, the level of his achievement should not matter. Even if he were a mediocre writer, his situation is the terrible concern of every fellow writer for, apart from his personal plight, what implications, what new threat against the carrier of the word does it bring? It should be the concern of individuals and above all, of governments and human rights organizations all over the world. With dictatorships apparently vanquished, this murderous new dictate invoking the power of international terrorism in the name of a great and respected religion should and can be dealt with only by democratic governments and the United Nations as an offense against humanity.

I return from the horrific singular threat to those that have been general for writers of this century now in its final, summing-up decade. In repressive regimes anywhere – whether in what was the Soviet bloc, Latin America, Africa, China – most imprisoned writers have been shut away for their activities as citizens striving for liberation against the oppression of the general society to which they belong. Others have been condemned by repressive regimes for serving society by writing as well as they can; for this aesthetic venture of ours becomes subversive when the shameful secrets of our times are explored deeply, with the artist’s rebellious integrity to the state of being manifest in life around her or him; then the writer’s themes and characters inevitably are formed by the pressures and distortions of that society as the life of the fisherman is determined by the power of the sea.

There is a paradox. In retaining this integrity, the writer sometimes must risk both the state’s indictment of treason, and the liberation forces’ complaint of lack of blind commitment. As a human being, no writer can stoop to the lie of Manichean ‘balance’. The devil always has lead in his shoes, when placed on his side of the scale. Yet, to paraphrase coarsely Márquez’s dictum given by him both as a writer and a fighter for justice, the writer must take the right to explore, warts and all, both the enemy and the beloved comrade in arms, since only a try for the truth makes sense of being, only a try for the truth edges towards justice just ahead of Yeats’s beast slouching to be born. In literature, from life,

we page through each other’s faces

we read each looking eye

… It has taken lives to be able to do so.

These are the words of the South African poet and fighter for justice and peace in our country, Mongane Serote. \\\\[13]

The writer is of service to humankind only insofar as the writer uses the word even against his or her own loyalties, trusts the state of being, as it is revealed, to hold somewhere in its complexity filaments of the cord of truth, able to be bound together, here and there, in art: trusts the state of being to yield somewhere fragmentary phrases of truth, which is the final word of words, never changed by our stumbling efforts to spell it out and write it down, never changed by lies, by semantic sophistry, by the dirtying of the word for the purposes of racism, sexism, prejudice, domination, the glorification of destruction, the curses and the praise-songs.

\\\\[1] “The God’s Script” from Labyrinths & Other Writings by Jorge Luis Borges. Translator unknown. Edited by Donald H. Yates & James E. Kirby. Penguin Modern Classics, page 71.

\\\\[2] Mythologies by Roland Barthes. Translated by Annette Lavers. Hill & Wang, page 131.

\\\\[3] Historie de Lynx by Claude Lévi-Strauss.’… je les situais à mi-chemin entre le conte de fées et le roman policier’. Plon, page 13.

\\\\[4] Report to Greco by Nikos Kazantzakis. Faber & Faber, page 150.

\\\\[5] S/Z by Roland Barthes. Translated by Richard Miller. Jonathan Cape.

\\\\[6] London Observer review. 19/4/81. Anthony Burgess.

\\\\[7] The Third Octavo Notebook from Wedding Preparations in the Country by Franz Kafka. Definitive Edition. Secker & Warburg.

\\\\[8] Carnets 1942-5 by Albert Camus.

\\\\[9] Gabriel Gárcia Márquez. In an interview; my notes do not give the journal or date.

\\\\[10] ‘Dedication’ from Selected Poems by Czeslaw Milosz. The Ecco Press.

\\\\[11] “To Posterity’ from Selected Poems by Bertolt Brecht. Translated by H. R. Hays. Grove Press, page 173.

\\\\[12] Report to Greco by Nikos Kazantzakis. Faber & Faber.

\\\\[13] A Tough Tale by Mongane Wally Serote. Kliptown Books.

From Nobel Lectures, Literature 1991-1995, Editor Sture Allén, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, 1997

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1991

TONI MORRISON, 1993

Nobel Lecture December 7, 1993

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. Blind but wise.” Or was it an old man? A guru, perhaps. Or a griot soothing restless children. I have heard this story, or one exactly like it, in the lore of several cultures.

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. Blind. Wise.”

In the version I know the woman is the daughter of slaves, black, American, and lives alone in a small house outside of town. Her reputation for wisdom is without peer and without question. Among her people she is both the law and its transgression. The honor she is paid and the awe in which she is held reach beyond her neighborhood to places far away; to the city where the intelligence of rural prophets is the source of much amusement.

One day the woman is visited by some young people who seem to be bent on disproving her clairvoyance and showing her up for the fraud they believe she is. Their plan is simple: they enter her house and ask the one question the answer to which rides solely on her difference from them, a difference they regard as a profound disability: her blindness. They stand before her, and one of them says, “Old woman, I hold in my hand a bird. Tell me whether it is living or dead.”

She does not answer, and the question is repeated. “Is the bird I am holding living or dead?”

Still she doesn’t answer. She is blind and cannot see her visitors, let alone what is in their hands. She does not know their color, gender or homeland. She only knows their motive.

The old woman’s silence is so long, the young people have trouble holding their laughter.

Finally she speaks and her voice is soft but stern. “I don’t know”, she says. “I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands. It is in your hands.”

Her answer can be taken to mean: if it is dead, you have either found it that way or you have killed it. If it is alive, you can still kill it. Whether it is to stay alive, it is your decision. Whatever the case, it is your responsibility.

For parading their power and her helplessness, the young visitors are reprimanded, told they are responsible not only for the act of mockery but also for the small bundle of life sacrificed to achieve its aims. The blind woman shifts attention away from assertions of power to the instrument through which that power is exercised.

Speculation on what (other than its own frail body) that bird-in-the-hand might signify has always been attractive to me, but especially so now thinking, as I have been, about the work I do that has brought me to this company. So I choose to read the bird as language and the woman as a practiced writer. She is worried about how the language she dreams in, given to her at birth, is handled, put into service, even withheld from her for certain nefarious purposes. Being a writer she thinks of language partly as a system, partly as a living thing over which one has control, but mostly as agency – as an act with consequences. So the question the children put to her: “Is it living or dead?” is not unreal because she thinks of language as susceptible to death, erasure; certainly imperiled and salvageable only by an effort of the will. She believes that if the bird in the hands of her visitors is dead the custodians are responsible for the corpse. For her a dead language is not only one no longer spoken or written, it is unyielding language content to admire its own paralysis. Like statist language, censored and censoring. Ruthless in its policing duties, it has no desire or purpose other than maintaining the free range of its own narcotic narcissism, its own exclusivity and dominance. However moribund, it is not without effect for it actively thwarts the intellect, stalls conscience, suppresses human potential. Unreceptive to interrogation, it cannot form or tolerate new ideas, shape other thoughts, tell another story, fill baffling silences. Official language smitheryed to sanction ignorance and preserve privilege is a suit of armor polished to shocking glitter, a husk from which the knight departed long ago. Yet there it is: dumb, predatory, sentimental. Exciting reverence in schoolchildren, providing shelter for despots, summoning false memories of stability, harmony among the public.

She is convinced that when language dies, out of carelessness, disuse, indifference and absence of esteem, or killed by fiat, not only she herself, but all users and makers are accountable for its demise. In her country children have bitten their tongues off and use bullets instead to iterate the voice of speechlessness, of disabled and disabling language, of language adults have abandoned altogether as a device for grappling with meaning, providing guidance, or expressing love. But she knows tongue-suicide is not only the choice of children. It is common among the infantile heads of state and power merchants whose evacuated language leaves them with no access to what is left of their human instincts for they speak only to those who obey, or in order to force obedience.

The systematic looting of language can be recognized by the tendency of its users to forgo its nuanced, complex, mid-wifery properties for menace and subjugation. Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek – it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language – all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.

The old woman is keenly aware that no intellectual mercenary, nor insatiable dictator, no paid-for politician or demagogue; no counterfeit journalist would be persuaded by her thoughts. There is and will be rousing language to keep citizens armed and arming; slaughtered and slaughtering in the malls, courthouses, post offices, playgrounds, bedrooms and boulevards; stirring, memorializing language to mask the pity and waste of needless death. There will be more diplomatic language to countenance rape, torture, assassination. There is and will be more seductive, mutant language designed to throttle women, to pack their throats like paté-producing geese with their own unsayable, transgressive words; there will be more of the language of surveillance disguised as research; of politics and history calculated to render the suffering of millions mute; language glamorized to thrill the dissatisfied and bereft into assaulting their neighbors; arrogant pseudo-empirical language crafted to lock creative people into cages of inferiority and hopelessness.

Underneath the eloquence, the glamor, the scholarly associations, however stirring or seductive, the heart of such language is languishing, or perhaps not beating at all – if the bird is already dead.

She has thought about what could have been the intellectual history of any discipline if it had not insisted upon, or been forced into, the waste of time and life that rationalizations for and representations of dominance required – lethal discourses of exclusion blocking access to cognition for both the excluder and the excluded.

The conventional wisdom of the Tower of Babel story is that the collapse was a misfortune. That it was the distraction, or the weight of many languages that precipitated the tower’s failed architecture. That one monolithic language would have expedited the building and heaven would have been reached. Whose heaven, she wonders? And what kind? Perhaps the achievement of Paradise was premature, a little hasty if no one could take the time to understand other languages, other views, other narratives period. Had they, the heaven they imagined might have been found at their feet. Complicated, demanding, yes, but a view of heaven as life; not heaven as post-life.

She would not want to leave her young visitors with the impression that language should be forced to stay alive merely to be. The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers. Although its poise is sometimes in displacing experience it is not a substitute for it. It arcs toward the place where meaning may lie. When a President of the United States thought about the graveyard his country had become, and said, “The world will little note nor long remember what we say here. But it will never forget what they did here,” his simple words are exhilarating in their life-sustaining properties because they refused to encapsulate the reality of 600, 000 dead men in a cataclysmic race war. Refusing to monumentalize, disdaining the “final word”, the precise “summing up”, acknowledging their “poor power to add or detract”, his words signal deference to the uncapturability of the life it mourns. It is the deference that moves her, that recognition that language can never live up to life once and for all. Nor should it. Language can never “pin down” slavery, genocide, war. Nor should it yearn for the arrogance to be able to do so. Its force, its felicity is in its reach toward the ineffable.

Be it grand or slender, burrowing, blasting, or refusing to sanctify; whether it laughs out loud or is a cry without an alphabet, the choice word, the chosen silence, unmolested language surges toward knowledge, not its destruction. But who does not know of literature banned because it is interrogative; discredited because it is critical; erased because alternate? And how many are outraged by the thought of a self-ravaged tongue?

Word-work is sublime, she thinks, because it is generative; it makes meaning that secures our difference, our human difference – the way in which we are like no other life.

We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.

“Once upon a time, …” visitors ask an old woman a question. Who are they, these children? What did they make of that encounter? What did they hear in those final words: “The bird is in your hands”? A sentence that gestures towards possibility or one that drops a latch? Perhaps what the children heard was “It’s not my problem. I am old, female, black, blind. What wisdom I have now is in knowing I cannot help you. The future of language is yours.”

They stand there. Suppose nothing was in their hands? Suppose the visit was only a ruse, a trick to get to be spoken to, taken seriously as they have not been before? A chance to interrupt, to violate the adult world, its miasma of discourse about them, for them, but never to them? Urgent questions are at stake, including the one they have asked: “Is the bird we hold living or dead?” Perhaps the question meant: “Could someone tell us what is life? What is death?” No trick at all; no silliness. A straightforward question worthy of the attention of a wise one. An old one. And if the old and wise who have lived life and faced death cannot describe either, who can?

But she does not; she keeps her secret; her good opinion of herself; her gnomic pronouncements; her art without commitment. She keeps her distance, enforces it and retreats into the singularity of isolation, in sophisticated, privileged space.

Nothing, no word follows her declaration of transfer. That silence is deep, deeper than the meaning available in the words she has spoken. It shivers, this silence, and the children, annoyed, fill it with language invented on the spot.

“Is there no speech,” they ask her, “no words you can give us that helps us break through your dossier of failures? Through the education you have just given us that is no education at all because we are paying close attention to what you have done as well as to what you have said? To the barrier you have erected between generosity and wisdom?

“We have no bird in our hands, living or dead. We have only you and our important question. Is the nothing in our hands something you could not bear to contemplate, to even guess? Don’t you remember being young when language was magic without meaning? When what you could say, could not mean? When the invisible was what imagination strove to see? When questions and demands for answers burned so brightly you trembled with fury at not knowing?

“Do we have to begin consciousness with a battle heroines and heroes like you have already fought and lost leaving us with nothing in our hands except what you have imagined is there? Your answer is artful, but its artfulness embarrasses us and ought to embarrass you. Your answer is indecent in its self-congratulation. A made-for-television script that makes no sense if there is nothing in our hands.

“Why didn’t you reach out, touch us with your soft fingers, delay the sound bite, the lesson, until you knew who we were? Did you so despise our trick, our modus operandi you could not see that we were baffled about how to get your attention? We are young. Unripe. We have heard all our short lives that we have to be responsible. What could that possibly mean in the catastrophe this world has become; where, as a poet said, “nothing needs to be exposed since it is already barefaced.” Our inheritance is an affront. You want us to have your old, blank eyes and see only cruelty and mediocrity. Do you think we are stupid enough to perjure ourselves again and again with the fiction of nationhood? How dare you talk to us of duty when we stand waist deep in the toxin of your past?

“You trivialize us and trivialize the bird that is not in our hands. Is there no context for our lives? No song, no literature, no poem full of vitamins, no history connected to experience that you can pass along to help us start strong? You are an adult. The old one, the wise one. Stop thinking about saving your face. Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story. Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created. We will not blame you if your reach exceeds your grasp; if love so ignites your words they go down in flames and nothing is left but their scald. Or if, with the reticence of a surgeon’s hands, your words suture only the places where blood might flow. We know you can never do it properly – once and for all. Passion is never enough; neither is skill. But try. For our sake and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don’t tell us what to believe, what to fear. Show us belief's wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear’s caul. You, old woman, blessed with blindness, can speak the language that tells us what only language can: how to see without pictures. Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names. Language alone is meditation.

“Tell us what it is to be a woman so that we may know what it is to be a man. What moves at the margin. What it is to have no home in this place. To be set adrift from the one you knew. What it is to live at the edge of towns that cannot bear your company.

“Tell us about ships turned away from shorelines at Easter, placenta in a field. Tell us about a wagonload of slaves, how they sang so softly their breath was indistinguishable from the falling snow. How they knew from the hunch of the nearest shoulder that the next stop would be their last. How, with hands prayered in their sex, they thought of heat, then sun. Lifting their faces as though it was there for the taking. Turning as though there for the taking. They stop at an inn. The driver and his mate go in with the lamp leaving them humming in the dark. The horse’s void steams into the snow beneath its hooves and its hiss and melt are the envy of the freezing slaves.

“The inn door opens: a girl and a boy step away from its light. They climb into the wagon bed. The boy will have a gun in three years, but now he carries a lamp and a jug of warm cider. They pass it from mouth to mouth. The girl offers bread, pieces of meat and something more: a glance into the eyes of the one she serves. One helping for each man, two for each woman. And a look. They look back. The next stop will be their last. But not this one. This one is warmed.”

It’s quiet again when the children finish speaking, until the woman breaks into the silence.

“Finally”, she says, “I trust you now. I trust you with the bird that is not in your hands because you have truly caught it. Look. How lovely it is, this thing we have done – together.”

From Nobel Lectures, Literature 1991-1995, Editor Sture Allén, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, 1997

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1993

Back to the StartNobel Lecture, December 7, 1996

The poet and the world

They say the first sentence in any speech is always the hardest. Well, that one’s behind me, anyway. But I have a feeling that the sentences to come – the third, the sixth, the tenth, and so on, up to the final line – will be just as hard, since I’m supposed to talk about poetry. I’ve said very little on the subject, next to nothing, in fact. And whenever I have said anything, I’ve always had the sneaking suspicion that I’m not very good at it. This is why my lecture will be rather short. All imperfection is easier to tolerate if served up in small doses.

Contemporary poets are skeptical and suspicious even, or perhaps especially, about themselves. They publicly confess to being poets only reluctantly, as if they were a little ashamed of it. But in our clamorous times it’s much easier to acknowledge your faults, at least if they’re attractively packaged, than to recognize your own merits, since these are hidden deeper and you never quite believe in them yourself … When filling in questionnaires or chatting with strangers, that is, when they can’t avoid revealing their profession, poets prefer to use the general term “writer” or replace “poet” with the name of whatever job they do in addition to writing. Bureaucrats and bus passengers respond with a touch of incredulity and alarm when they find out that they’re dealing with a poet. I suppose philosophers may meet with a similar reaction. Still, they’re in a better position, since as often as not they can embellish their calling with some kind of scholarly title. Professor of philosophy – now that sounds much more respectable.

But there are no professors of poetry. This would mean, after all, that poetry is an occupation requiring specialized study, regular examinations, theoretical articles with bibliographies and footnotes attached, and finally, ceremoniously conferred diplomas. And this would mean, in turn, that it’s not enough to cover pages with even the most exquisite poems in order to become a poet. The crucial element is some slip of paper bearing an official stamp. Let us recall that the pride of Russian poetry, the future Nobel Laureate Joseph Brodsky was once sentenced to internal exile precisely on such grounds. They called him “a parasite,” because he lacked official certification granting him the right to be a poet…

Several years ago, I had the honor and pleasure of meeting Brodsky in person. And I noticed that, of all the poets I’ve known, he was the only one who enjoyed calling himself a poet. He pronounced the word without inhibitions.

Just the opposite – he spoke it with defiant freedom. It seems to me that this must have been because he recalled the brutal humiliations he had experienced in his youth.

In more fortunate countries, where human dignity isn’t assaulted so readily, poets yearn, of course, to be published, read, and understood, but they do little, if anything, to set themselves above the common herd and the daily grind. And yet it wasn’t so long ago, in this century’s first decades, that poets strove to shock us with their extravagant dress and eccentric behavior. But all this was merely for the sake of public display. The moment always came when poets had to close the doors behind them, strip off their mantles, fripperies, and other poetic paraphernalia, and confront – silently, patiently awaiting their own selves – the still white sheet of paper. For this is finally what really counts.

It’s not accidental that film biographies of great scientists and artists are produced in droves. The more ambitious directors seek to reproduce convincingly the creative process that led to important scientific discoveries or the emergence of a masterpiece. And one can depict certain kinds of scientific labor with some success. Laboratories, sundry instruments, elaborate machinery brought to life: such scenes may hold the audience’s interest for a while. And those moments of uncertainty – will the experiment, conducted for the thousandth time with some tiny modification, finally yield the desired result? – can be quite dramatic. Films about painters can be spectacular, as they go about recreating every stage of a famous painting’s evolution, from the first penciled line to the final brush-stroke. Music swells in films about composers: the first bars of the melody that rings in the musician’s ears finally emerge as a mature work in symphonic form. Of course this is all quite naive and doesn’t explain the strange mental state popularly known as inspiration, but at least there’s something to look at and listen to.

But poets are the worst. Their work is hopelessly unphotogenic. Someone sits at a table or lies on a sofa while staring motionless at a wall or ceiling. Once in a while this person writes down seven lines only to cross out one of them fifteen minutes later, and then another hour passes, during which nothing happens … Who could stand to watch this kind of thing?

I’ve mentioned inspiration. Contemporary poets answer evasively when asked what it is, and if it actually exists. It’s not that they’ve never known the blessing of this inner impulse. It’s just not easy to explain something to someone else that you don’t understand yourself.

When I’m asked about this on occasion, I hedge the question too. But my answer is this: inspiration is not the exclusive privilege of poets or artists generally. There is, has been, and will always be a certain group of people whom inspiration visits. It’s made up of all those who’ve consciously chosen their calling and do their job with love and imagination. It may include doctors, teachers, gardeners – and I could list a hundred more professions. Their work becomes one continuous adventure as long as they manage to keep discovering new challenges in it. Difficulties and setbacks never quell their curiosity. A swarm of new questions emerges from every problem they solve. Whatever inspiration is, it’s born from a continuous “I don’t know.”

There aren’t many such people. Most of the earth’s inhabitants work to get by. They work because they have to. They didn’t pick this or that kind of job out of passion; the circumstances of their lives did the choosing for them. Loveless work, boring work, work valued only because others haven’t got even that much, however loveless and boring – this is one of the harshest human miseries. And there’s no sign that coming centuries will produce any changes for the better as far as this goes.

And so, though I may deny poets their monopoly on inspiration, I still place them in a select group of Fortune’s darlings.

At this point, though, certain doubts may arise in my audience. All sorts of torturers, dictators, fanatics, and demagogues struggling for power by way of a few loudly shouted slogans also enjoy their jobs, and they too perform their duties with inventive fervor. Well, yes, but they “know.” They know, and whatever they know is enough for them once and for all. They don’t want to find out about anything else, since that might diminish their arguments’ force. And any knowledge that doesn’t lead to new questions quickly dies out: it fails to maintain the temperature required for sustaining life. In the most extreme cases, cases well known from ancient and modern history, it even poses a lethal threat to society.

This is why I value that little phrase “I don’t know” so highly. It’s small, but it flies on mighty wings. It expands our lives to include the spaces within us as well as those outer expanses in which our tiny Earth hangs suspended. If Isaac Newton had never said to himself “I don’t know,” the apples in his little orchard might have dropped to the ground like hailstones and at best he would have stooped to pick them up and gobble them with gusto. Had my compatriot Marie Skłodowska-Curie never said to herself “I don’t know”, she probably would have wound up teaching chemistry at some private high school for young ladies from good families, and would have ended her days performing this otherwise perfectly respectable job. But she kept on saying “I don’t know,” and these words led her, not just once but twice, to Stockholm, where restless, questing spirits are occasionally rewarded with the Nobel Prize.

Poets, if they’re genuine, must also keep repeating “I don’t know.” Each poem marks an effort to answer this statement, but as soon as the final period hits the page, the poet begins to hesitate, starts to realize that this particular answer was pure makeshift that’s absolutely inadequate to boot. So the poets keep on trying, and sooner or later the consecutive results of their self-dissatisfaction are clipped together with a giant paperclip by literary historians and called their “oeuvre”…

I sometimes dream of situations that can’t possibly come true. I audaciously imagine, for example, that I get a chance to chat with the Ecclesiastes, the author of that moving lament on the vanity of all human endeavors. I would bow very deeply before him, because he is, after all, one of the greatest poets, for me at least. That done, I would grab his hand. “‘There’s nothing new under the sun’: that’s what you wrote, Ecclesiastes. But you yourself were born new under the sun. And the poem you created is also new under the sun, since no one wrote it down before you. And all your readers are also new under the sun, since those who lived before you couldn’t read your poem. And that cypress that you’re sitting under hasn’t been growing since the dawn of time. It came into being by way of another cypress similar to yours, but not exactly the same. And Ecclesiastes, I’d also like to ask you what new thing under the sun you’re planning to work on now? A further supplement to the thoughts you’ve already expressed? Or maybe you’re tempted to contradict some of them now? In your earlier work you mentioned joy – so what if it’s fleeting? So maybe your new-under-the-sun poem will be about joy? Have you taken notes yet, do you have drafts? I doubt you’ll say, ‘I’ve written everything down, I’ve got nothing left to add.’ There’s no poet in the world who can say this, least of all a great poet like yourself.”

The world – whatever we might think when terrified by its vastness and our own impotence, or embittered by its indifference to individual suffering, of people, animals, and perhaps even plants, for why are we so sure that plants feel no pain; whatever we might think of its expanses pierced by the rays of stars surrounded by planets we’ve just begun to discover, planets already dead? still dead? we just don’t know; whatever we might think of this measureless theater to which we’ve got reserved tickets, but tickets whose lifespan is laughably short, bounded as it is by two arbitrary dates; whatever else we might think of this world – it is astonishing.

But “astonishing” is an epithet concealing a logical trap. We’re astonished, after all, by things that deviate from some well-known and universally acknowledged norm, from an obviousness we’ve grown accustomed to. Now the point is, there is no such obvious world. Our astonishment exists per se and isn’t based on comparison with something else.

Granted, in daily speech, where we don’t stop to consider every word, we all use phrases like “the ordinary world,” “ordinary life,” “the ordinary course of events” … But in the language of poetry, where every word is weighed, nothing is usual or normal. Not a single stone and not a single cloud above it. Not a single day and not a single night after it. And above all, not a single existence, not anyone’s existence in this world.

It looks like poets will always have their work cut out for them.

Translated from Polish by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1996

Back to the StartDORIS LESSING, 2007

December 7, 2007

On not winning the Nobel Prize

I am standing in a doorway looking through clouds of blowing dust to where I am told there is still uncut forest. Yesterday I drove through miles of stumps, and charred remains of fires where, in ’56, there was the most wonderful forest I have ever seen, all now destroyed. People have to eat. They have to get fuel for fires.

This is north-west Zimbabwe in the early eighties, and I am visiting a friend who was a teacher in a school in London. He is here “to help Africa,” as we put it. He is a gently idealistic soul and what he found in this school shocked him into a depression, from which it was hard to recover. This school is like every other built after Independence. It consists of four large brick rooms side by side, put straight into the dust, one two three four, with a half room at one end, which is the library. In these classrooms are blackboards, but my friend keeps the chalks in his pocket, as otherwise they would be stolen. There is no atlas or globe in the school, no textbooks, no exercise books, or biros. In the library there are no books of the kind the pupils would like to read, but only tomes from American universities, hard even to lift, rejects from white libraries, or novels with titles like Weekend in Paris and Felicity Finds Love.

There is a goat trying to find sustenance in some aged grass. The headmaster has embezzled the school funds and is suspended, arousing the question familiar to all of us but usually in more august contexts: How is it these people behave like this when they must know everyone is watching them?

My friend doesn’t have any money because everyone, pupils and teachers, borrow from him when he is paid and will probably never pay him back. The pupils range from six to twenty-six, because some who did not get schooling as children are here to make it up. Some pupils walk many miles every morning, rain or shine and across rivers. They cannot do homework because there is no electricity in the villages, and you can’t study easily by the light of a burning log. The girls have to fetch water and cook before they set off for school and when they get back.

As I sit with my friend in his room, people drop in shyly, and everyone begs for books. “Please send us books when you get back to London,” one man says. “They taught us to read but we have no books.” Everybody I met, everyone, begged for books.

I was there some days. The dust blew. The pumps had broken and the women were having to fetch water from the river. Another idealistic teacher from England was rather ill after seeing what this “school” was like.

On the last day they slaughtered the goat. They cut it into bits and cooked it in a great tin. This was the much anticipated end-of-term feast: boiled goat and porridge. I drove away while it was still going on, back through the charred remains and stumps of the forest.

I do not think many of the pupils of this school will get prizes.

The next day I am to give a talk at a school in North London, a very good school, whose name we all know. It is a school for boys, with beautiful buildings and gardens.

These children here have a visit from some well known person every week, and it is in the nature of things that these may be fathers, relatives, even mothers of the pupils. A visit from a celebrity is not unusual for them.

As I talk to them, the school in the blowing dust of north-west Zimbabwe is in my mind, and I look at the mildly expectant English faces in front of me and try to tell them about what I have seen in the last week. Classrooms without books, without textbooks, or an atlas, or even a map pinned to a wall. A school where the teachers beg to be sent books to tell them how to teach, they being only eighteen or nineteen themselves. I tell these English boys how everybody begs for books: “Please send us books.” I am sure that anyone who has ever given a speech will know that moment when the faces you are looking at are blank. Your listeners cannot hear what you are saying, there are no images in their minds to match what you are telling them – in this case the story of a school standing in dust clouds, where water is short, and where the end of term treat is a just-killed goat cooked in a great pot.

Is it really so impossible for these privileged students to imagine such bare poverty?

I do my best. They are polite.

I’m sure that some of them will one day win prizes.

Then, the talk is over. Afterwards I ask the teachers how the library is, and if the pupils read. In this privileged school, I hear what I always hear when I go to such schools and even universities.

“You know how it is,” one of the teacher’s says. “A lot of the boys have never read at all, and the library is only half used.”

Yes, indeed we do know how it is. All of us.

We are in a fragmenting culture, where our certainties of even a few decades ago are questioned and where it is common for young men and women, who have had years of education, to know nothing of the world, to have read nothing, knowing only some speciality or other, for instance, computers.

What has happened to us is an amazing invention — computers and the internet and TV. It is a revolution. This is not the first revolution the human race has dealt with. The printing revolution, which did not take place in a matter of a few decades, but took much longer, transformed our minds and ways of thinking. A foolhardy lot, we accepted it all, as we always do, never asked, What is going to happen to us now, with this invention of print? In the same way, we never thought to ask, How will our lives, our way of thinking, be changed by this internet, which has seduced a whole generation with its inanities so that even quite reasonable people will confess that once they are hooked, it is hard to cut free, and they may find a whole day has passed in blogging etc.

Very recently, anyone even mildly educated would respect learning, education, and our great store of literature. Of course, we all know that when this happy state was with us, people would pretend to read, would pretend respect for learning. But it is on record that working men and women longed for books, and this is evidenced by the founding of working men’s libraries and institutes, the colleges of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Reading, books, used to be part of a general education.

Older people, talking to young ones, must understand just how much of an education reading was, because the young ones know so much less. And if children cannot read, it is because they have not read.

We all know this sad story.

But we do not know the end of it.

We think of the old adage, “Reading maketh a full man” – and forgetting about jokes to do with over-eating – reading makes a woman and a man full of information, of history, of all kinds of knowledge.

But we in the West are not the only people in the world. Not long ago a friend who had been in Zimbabwe told me about a village where people had not eaten for three days, but they were still talking about books and how to get them, about education.

I belong to an organisation which started out with the intention of getting books into the villages. There was a group of people who in another connection had travelled Zimbabwe at its grass roots. They told me that the villages, unlike what is reported, are full of intelligent people, teachers retired, teachers on leave, children on holidays, old people. I myself paid for a little survey to discover what people in Zimbabwe want to read, and found the results were the same as those of a Swedish survey I had not known about. People want to read the same kinds of books that we in Europe want to read – novels of all kinds, science fiction, poetry, detective stories, plays, and do-it-yourself books, like how to open a bank account. All of Shakespeare too. A problem with finding books for villagers is that they don’t know what is available, so a set book, like the Mayor of Casterbridge, becomes popular simply because it just happens to be there. Animal Farm, for obvious reasons, is the most popular of all novels.

Our organisation was helped from the very start by Norway, and then by Sweden. Without this kind of support our supplies of books would have dried up. We got books from wherever we could. Remember, a good paperback from England costs a month’s wages in Zimbabwe: that was before Mugabe’s reign of terror. Now with inflation, it would cost several years’ wages. But having taken a box of books out to a village – and remember there is a terrible shortage of petrol – I can tell you that the box was greeted with tears. The library may be a plank on bricks under a tree. And within a week there will be literacy classes – people who can read teaching those who can’t, citizenship classes – and in one remote village, since there were no novels written in the language Tonga, a couple of lads sat down to write novels in Tonga. There are six or so main languages in Zimbabwe and there are novels in all of them: violent, incestuous, full of crime and murder.

It is said that a people gets the government it deserves, but I do not think it is true of Zimbabwe. And we must remember that this respect and hunger for books comes, not from Mugabe’s regime, but from the one before it, the whites. It is an astonishing phenomenon, this hunger for books, and it can be seen everywhere from Kenya down to the Cape of Good Hope.

This links improbably with a fact: I was brought up in what was virtually a mud hut, thatched. This kind of house has been built always, everywhere there are reeds or grass, suitable mud, poles for walls. Saxon England for example. The one I was brought up in had four rooms, one beside another, and it was full of books. Not only did my parents take books from England to Africa, but my mother ordered books by post from England for her children. Books arrived in great brown paper parcels, and they were the joy of my young life. A mud hut, but full of books.

Even today I get letters from people living in a village that might not have electricity or running water, just like our family in our elongated mud hut. “I shall be a writer too,” they say, “because I’ve the same kind of house you lived in.”

But here is the difficulty, no?

Writing, writers, do not come out of houses without books.

There is the gap. There is the difficulty.

I have been looking at the speeches by some of your recent prizewinners. Take the magnificent Pamuk. He said his father had 500 books. His talent did not come out of the air, he was connected with the great tradition.

Take V.S. Naipaul. He mentions that the Indian Vedas were close behind the memory of his family. His father encouraged him to write, and when he got to England he would visit the British Library. So he was close to the great tradition.

Let us take John Coetzee. He was not only close to the great tradition, he was the tradition: he taught literature in Cape Town. And how sorry I am that I was never in one of his classes, taught by that wonderfully brave, bold mind.

In order to write, in order to make literature, there must be a close connection with libraries, books, with the Tradition.

I have a friend from Zimbabwe, a Black writer. He taught himself to read from the labels on jam jars, the labels on preserved fruit cans. He was brought up in an area I have driven through, an area for rural blacks. The earth is grit and gravel, there are low sparse bushes. The huts are poor, nothing like the well cared-for huts of the better off. A school – but like one I have described. He found a discarded children’s encyclopaedia on a rubbish heap and taught himself from that.

On Independence in 1980 there was a group of good writers in Zimbabwe, truly a nest of singing birds. They were bred in old Southern Rhodesia, under the whites – the mission schools, the better schools. Writers are not made in Zimbabwe. Not easily, not under Mugabe.

All the writers travelled a difficult road to literacy, let alone to becoming writers. I would say learning to read from the printed labels on jam jars and discarded encyclopaedias was not uncommon. And we are talking about people hungering for standards of education beyond them, living in huts with many children – an overworked mother, a fight for food and clothing.

Yet despite these difficulties, writers came into being. And we should also remember that this was Zimbabwe, conquered less than a hundred years before. The grandparents of these people might have been storytellers working in the oral tradition. In one or two generations there was the transition from stories remembered and passed on, to print, to books. What an achievement.

Books, literally wrested from rubbish heaps and the detritus of the white man’s world. But a sheaf of paper is one thing, a published book quite another. I have had several accounts sent to me of the publishing scene in Africa. Even in more privileged places like North Africa, with its different tradition, to talk of a publishing scene is a dream of possibilities.

Here I am talking about books never written, writers that could not make it because the publishers are not there. Voices unheard. It is not possible to estimate this great waste of talent, of potential. But even before that stage of a book’s creation which demands a publisher, an advance, encouragement, there is something else lacking.

Writers are often asked, How do you write? With a word processor? an electric typewriter? a quill? longhand? But the essential question is, “Have you found a space, that empty space, which should surround you when you write?” Into that space, which is like a form of listening, of attention, will come the words, the words your characters will speak, ideas – inspiration.

If a writer cannot find this space, then poems and stories may be stillborn.